We just returned from a Turman family reunion. The people in attendance were descendants of Manford Cleveland and Sarah Elizabeth Turman, who had homesteaded in Southeastern Idaho in the early 1900s.

It was a wonderful opportunity to renew relationships with relatives rarely seen (wow, say that a few times very fast). There were representatives of all five branches of the family and so we all had a chance to share family stories, legends, and tall tales.

One of the most fascinating things from a historian’s point of view was the perspective of different members who had been told family stories by their parents and grandparents. Of course, there was a difference in the ages and circumstances of the original participants, but also a personal basis to make their family member into a hero, or at least seen in a favorable light.

Or just the opposite.

I was the youngest, by many years, to my oldest brother. In my memory, it seems a vivid memory of the pain my parents felt when he got in trouble as a young man and they were called to bail him out of jail. As a young child, I felt resentment and embarrassment because his exploits were in the local newspaper. For the last fifty years, I could have sworn he was a narcissistic and selfish son and brother. While I loved him, I still felt a simmering resentment.

Imagine my surprise to find one of his contemporary cousins, who remembered him as a young man of great generosity and sensitivity. He shared a side of my brother that I had never experienced. He gave me examples of his kindness and fun-loving activities.

Hmm, perhaps I need to have some forgiveness in my heart. Do I have the right to my memories? Absolutely. But, is it possible, there was a different side to the story? In writing my memoir, perhaps it is a fair position to tell both versions. You, too, will find emotions and feelings bubbling up in your heart as you do this therapeutic work.

Professional Family Historians

One of the most fascinating people at the reunion had a degree in Researching Family Histories. What? Who even knew that was a real thing? But it is.

She taught me how to research county records for homestead boundaries, wills, lawsuits, census records, ship manifests, church records, Wikipedia, obituaries, and newspapers. She also taught me how important it is to couch your story in the history of the times.

Just a quick search of the Internet gave this information from the National Archives:

“The Homestead Act, enacted during the Civil War in 1862, provided that any adult citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government could claim 160 acres of surveyed government land. Claimants were required to “improve” the plot by building a dwelling and cultivating the land. After 5 years on the land, the original filer was entitled to the property, free and clear, except for a small registration fee. The title could also be acquired after only a 6-month residency and trivial improvements provided the claimant paid the government $1.25 per acre. After the Civil War, Union soldiers could deduct the time they had served from the residency requirements.

Unfortunately, the act was framed so ambiguously that it seemed to invite fraud, and early modifications by Congress only compounded the problem. Most of the land went to speculators, cattlemen, miners, lumbermen, and railroads. Of some 500 million acres dispersed by the General Land Office between 1862 and 1904, only 80 million acres went to homesteaders.”

Why Do Research For Your Memoir?

Don’t take it for granted that the lives of your ancestors are lost forever. There is evidence somewhere of the people they were and the tragedies and triumphs they experienced.

The research adds to the tapestry of your story. It gives a background that is readily understandable to the reader. Finding out the history builds understanding and inspires intergenerational storytelling and sharing. Learning about common ancestors and their lives has a way of opening up doors of communication and connection.

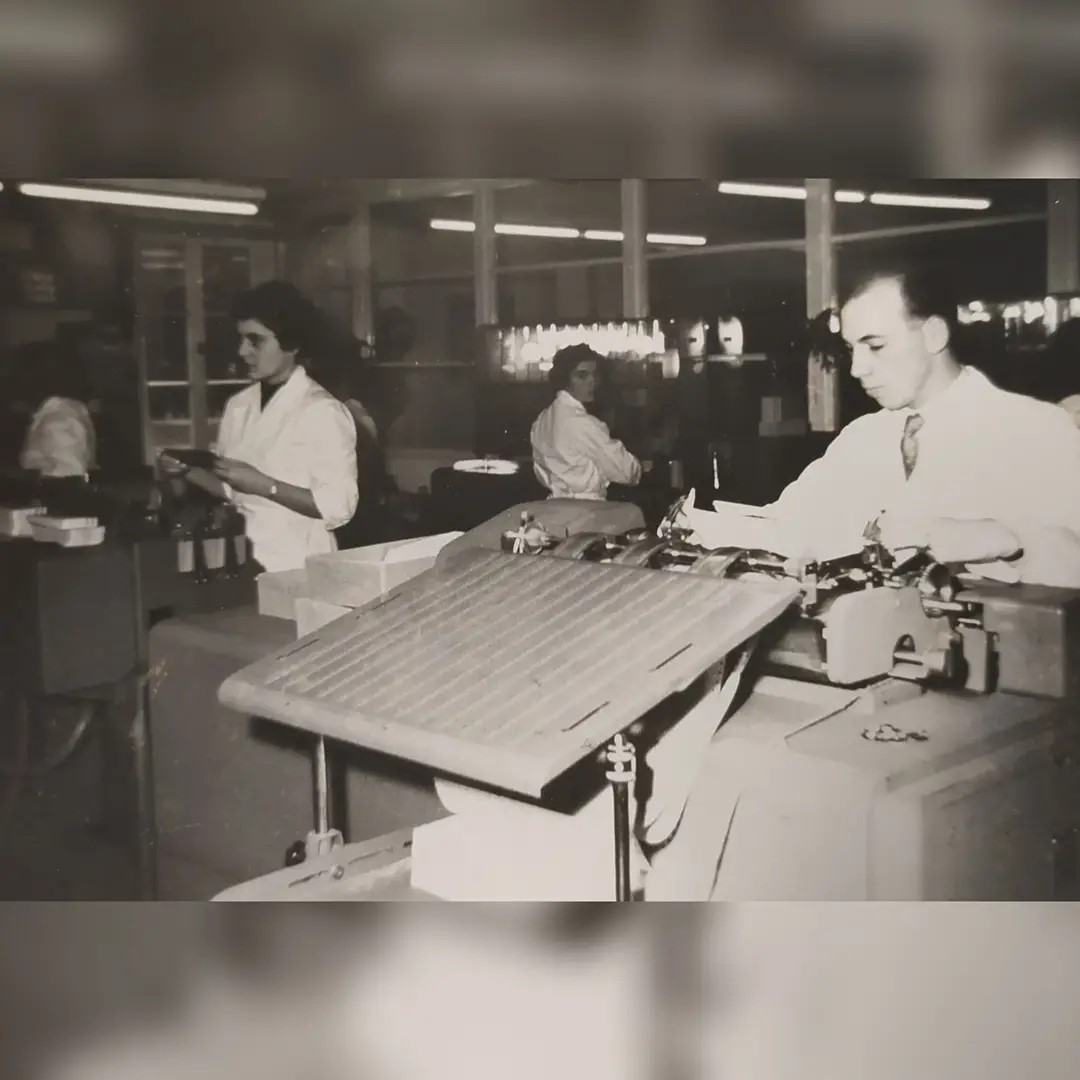

View this post on Instagram

There is a need for more family histories about families who are not affluent. Perhaps the story you are called to write is not about the ancestor who was the Senator, but rather the house cook who emigrated from Ireland in the steerage of a ship. There has not been nearly enough written about the females who helped to shape the history of the country and certainly the history of your family.

Those who did genealogical work in the past usually focused on the more affluent. It was easier to research and felt better to brag about. However, in my humble opinion as a reader, I would much rather learn about those who were immigrants, landless, illiterate, or self-made men, and women.